Souvenirs from Switzerland: Reflections on an Exchange Year

BY MARTIN PINCKNEY

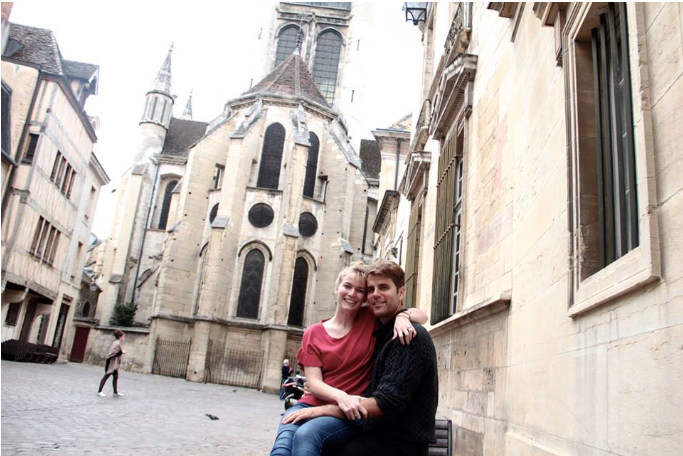

Shortly after my wife and I returned from a Master’s Exchange year with the theology faculty at the University of Bern in Switzerland, a professor at my home seminary asked me to share some key “take-aways” from my experience. As I tried to reconstruct for him what these might be, an acute sense of sadness came over me. After all, “take-aways” seemed to imply that I had brought the most valuable pieces home, whereas I felt the better parts of me were still there: walking those streets, sitting in those classrooms and churches, having homecooked dinners with guests in our little Swiss garden. I sometimes wonder if this same feeling was upon the gospel writers when they composed some of the moments and words of their Savior in the present tense: a tacit acknowledgment of their sense of the person and communion that abides with and in them. While English won’t allow the same temporal flexibility as biblical Greek, I will attempt to share with you the following “take-aways” — my souvenirs from Switzerland — in the language of that which abides.

Switzerland is beautiful, the kind of beauty that abides in you. I don’t merely mean its countryside and cities, but even its more mundane ways of living. Prior to arriving, I was inclined to think of the Swiss as further down the “slippery slope” of secularization, but then I quickly discovered a people who continue to measure their lives by a liturgical calendar our American social conscious and enterprising spirit have long forgotten. Stores are closed on Sundays. Advent is celebrated daily with small gifts, caroling, and Christmas markets. You can set your watch (or just leave it at home) to the ringing of church bells. While I’m sure their church leaders are calling for a return to the “reason of the season(s),” I cannot help but think we have much to learn from a culture that still finds ways to commemorate, preserve, and enjoy life — even in “ordinary time.”

Secondly, I tasted a small part of what it is like to be an outsider and a foreigner. In order to fulfill the requirements of my wife’s visa, I had to spend six lonely weeks paving the way for her arrival. Navigating a complex bureaucratic immigration system, finding a place to live, opening a Swiss bank account (quite the task for an American as it turns out)—all in a language and culture in which I was not yet fluent — often left me feeling frustrated and alienated. At the same time, I was conscious of the fact the obstacles I faced paled by comparison to many immigrants to my own country. Thus, I have an abiding respect, admiration, and empathy for those who truly immigrate.

Finally, I gained theological perspective that would never have been possible without venturing outside of my Protestant North American context. My studies stretched my understandings of what it means to be a disciple of Jesus and introduced me to new and striking images articulating the life we share in Christ. Put another way, I learned that the Church of Jesus Christ does not belong to me. This of course I already knew, but in my time at Bern, and also in visits to the Bossey Ecumenical Institute and the World Council of Churches, I saw Christians break bread together who could not be more different from one another culturally or doctrinally. In their words, their songs, the way they listened to one another and sought to work together, I saw people with hearts for Christ committed to abiding in and by his last great commandment — to love one another.

Martin Pinckney is a Master of Divinity student at Union Presbyterian Seminary.