Leadership Change and Theological Shifts: John Holt Rice and the Spirituality of the Church

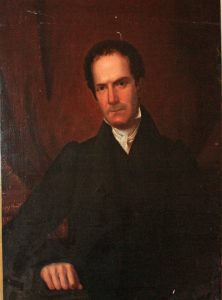

John Holt Rice followed Hoge into theological leadership at Hampden-Sydney. In 1821, Rice was named the Seminary’s theology professor by Hanover Presbytery. Agent for the theological library, member of the Hampden-Sydney Board of Trustees, a founder of the American Bible Society, publisher of the most prominent religious magazine in the South, and the successful pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Richmond, Rice was simultaneously offered the presidency of the College of New Jersey, which would become Princeton University. In Princeton he would have made more money and enjoyed more fame. He chose instead to build up a nearly abandoned theological school in a remote part of Virginia.5 His stature, connections, worldview, and energy gave the new seminary a chance to flourish and the potential to make significant theological and social change. Indeed, Rice maintained that seminaries are beneficial to society as the agents of reform and improvement.

As with Hoge, however, where racial justice was concerned, matters of social reform and improvement were complicated. In the matter of race, Rice himself had a complicated history. Licensed to preach by Hanover Presbytery in 1803, he was ordained to the service of the Cub Creek Church in Charlotte Court House, Virginia, where he served for eight years. He ran a farm with the work of enslaved persons that his wife had inherited. Under his leadership, Cub Creek Church grew from 58 white and 55 black parishioners to about 400 white and 100 black members.6

Rice published many articles denouncing the enslavement of human beings. The article for which he is best known appeared as “Thoughts on Slavery” in The Virginia Evangelical and Literary Magazinein 1819. Rice was clear: “It is to be generally admitted that slavery is the greatest political evil which has ever entered the United States.”7 Immediate emancipation was, however, out of the question. Indeed, Rice went on to opine that, “perhaps domestic emancipation will always be impracticable.”8 Like Hoge, Rice believed that the long-term goal should be repatriation of enslaved persons to Africa, because “we never can give them here the rights of citizenship.”9 Ultimately, with Hoge, Rice became a charter member of the American Colonization Society at Hampden-Sydney. He was criticized for his “liberalism.”

Despite his perceived liberalism on the issue, Rice helped craft a theological perspective later known as “The Spirituality of the Church.” While this view did not endorse slavery, it did champion the belief that the church should have nothing to say on such critical social matters, insisting on “the importance of the church keeping quite out of politics.” While Rice believed that enslaving human beings was an act of evil, he also championed the thought “that heated agitation of that question was an evil.”10 Further, since the New Testament tolerated human enslavement in its context, the practice in the American South should be considered comparably. Rice wrote:

The reason why I am so strenuously opposed to any movement by the church, or the ministers of religion on this subject, is simply this. I am convinced that anything we can do will injure religion, and retard the march of public feeling in relation to slavery. … Slaves by law are held as property. If the church or the minister of religion touches the subject, it is touching what are called the rights of property. The jealousy among our countrymen on this subject is such, that we cannot move a step in this way, without wakening up the strongest opposition, and producing the most violent excitement. The whole mass of the community will be set in motion, and the great body of the church will be carried along. Under this conviction, I wish the ministers of religion to be convinced that there is nothing in the New Testament which obliges them to take hold of this subject directly. In fact, I believe that it never has fared well with either church or state, when the church meddled with temporal affairs. And I should – knowing how unmanageable religious feeling is when not kept under the immediate influence of divine truth – be exceedingly afraid to see it brought to bear directly on the subject of slavery. Where the movement might end, I could not pretend to conjecture.11

The trend in this ominous direction was firmly fixed with the call to Union Theological Seminary of J. H. Rice’s successor, George Baxter. Under Baxter’s leadership, Union became a bastion of regionalism. Baxter reoriented Rice’s vision of gradual emancipation and colonization (deportation) as Union cooperated in extending the institution of human enslavement. In the spring of 1818, before the Presbytery of Lexington, Baxter led the committee that argued against the Presbyterian General Assembly’s pronouncement condemning human enslavement, maintaining that the enslavement of human beings was in accordance with Scripture.12

Throughout his teaching ministry at Union, Baxter consistently advocated the prevailing southern position on human enslavement. The basic position was simple: human enslavement was an institution founded in the providence of God and the church could not judge the morality of enslaving human beings, except to counsel the slave-owner to instruct his enslaved persons on religious matters,13 because the enslavement of human beings was legal.

Dr. William E. Thompson (B.D. 1962) argued that not only did other seminary faculty members enslave human beings, the Seminary itself may also have enslaved humans of African descent; there are references in the faculty minutes prior to the Civil War to “servants of the Seminary.” For example, Mrs. Thomas Miller kept the refectory in Steward’s Hall for the theological students. She was often angry about the people she enslaved, accusing them of “back-biting.” There is one entry in which Mrs. Miller continued to read her Bible in order to block out the screams of an enslaved person she had directed to be whipped.14

Contrary to Thompson, Sweetser notes that he was never able to find any documentation that the seminary owned or rented people who had been enslaved. He suspects that some students brought enslaved persons with them to the seminary and that the enslaved persons worked off the tuition of the students. According to the journal of one student, B.M. Smith, enslaved persons worked at jobs assigned by the seminary. Sweetser also argues that Mrs. Miller was a private contractor and that the people she enslaved would have had no connection to the seminary.

5. William Maxwell, A Memoir of the Rev. John Holt Rice, D.D. (J. Whetham, 1835), 232-33.

6. Ernest Trice Thompson, “John Holt Rice,” Union Seminary Review43/2 (January 1932), 177.

7. John Holt Rice, “Thoughts on Slavery,” The Virginia Evangelical and Literary Magazine 2/7 (July 1819), 293.

8. Rice, 295.

9. Rice, 301.

10. Alfred J. Morrison, “The Virginia Literary and Evangelical Magazine, 1818-1828,” The William and Mary Quarterly19/4 (April 1911), 270.

11. Maxwell, 307. See also Ernest Trice Thompson, The Spirituality of the Church : A Distinctive Doctrine of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (John Knox Press, 1961), 20-21, 25.

12. Ernest Trice Thompson, Presbyterians in the South, Volume 1, 1607-1861 (Richmond, VA: John Knox Press, 1963), 331.

13. Parker, United Synod of the South, 13-14.

14. William E. Thompson, “The Seminary Moves to Richmond, Pt. 4,” Museum : The Newsletter of the Associates of the Esther Thomas Atkinson Museum of Hampden-Sydney (Spring 2001), 39.