Reading Revelation through the Trials of Phillis Wheatley

By Rev. Dr. Larry L. Enis (Ph.D. ’13, Th.M. ’04)

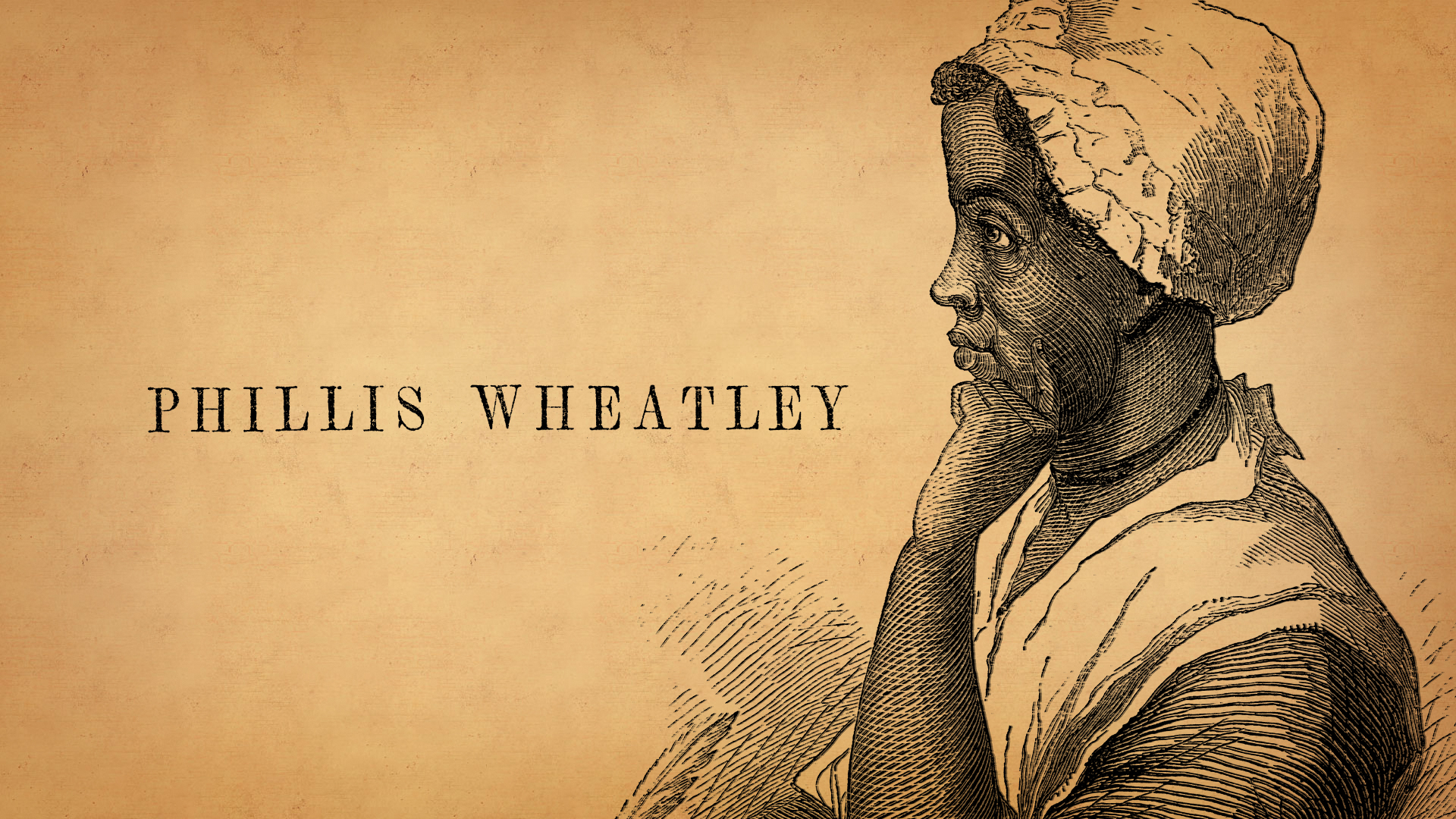

On October 8, 1772, this slim African slave in her late teens meets with eighteen of the most powerful, revered white men in Boston (1). Among this distinguished group of men, seven are ordained ministers, three are poets, many are recognized figures in America’s battle for independence, and several are slave-owning Harvard graduates. As she clutches a manuscript of poems she had written, this gentle African slave by the name of Phillis Wheatley, who would become recognized as America’s first black person to publish a book of poetry, is on trial. This privileged assembly of jurors has taken on the task of judging whether or not the Negro is capable of producing literature. Wheatley’s testimony, therefore, has implications not just for herself, but for the entire race of black people.

When we employ Wheatley’s trial as a focusing hermeneutical lens for examining the book of Revelation, the significance of testimony rises to the surface. In Revelation 1:9, John, the author of Revelation, writes to fellow Christians, “I, John, your brother who share with you in Jesus the persecution and the kingdom and the patient endurance, was on the island called Patmos because of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus.” Here, when John speaks of testimony, he is calling attention to the lordship of Jesus. Just a few verses earlier, in v. 5, John establishes Jesus as a conqueror of death, “ruler of the kings of the earth,” and deliverer “from our sins.” This is John’s testimony, and it is John’s hope that this is our testimony as well. John’s objective is to persuade readers to follow his lead in resisting the dominant culture by bearing witness to the lordship of Jesus.

Use of Wheatley’s story as a reading lens also illuminates the reality of displacement. In 1761, eleven years before Wheatley is on trial before dignitaries in Boston, she is snatched from her village in Africa, and then forced into a boat. As she and other Africans are transported through the Middle Passage—the journey from Africa to America across the Atlantic Ocean—this seven-year-old girl presumably witnesses events to which no kid should be exposed. Packed like sardines to maximize financial profit, Africans would be stripped of their clothing so as to facilitate the process of cleaning them (2). Africans who refused to eat willingly ran the risk of having their teeth broken by devices used to force-feed them. In some cases, the barbaric conditions of the Middle Passage compelled traumatized Africans to commit suicide by jumping overboard.

Finally, on July 11, 1761, after being stripped from her family and her home, after enduring the nightmare of the Middle Passage, this enslaved teenage African girl arrives in Boston (3). A wealthy woman by the name of Susanna Wheatley reads an advertisement for a house slave in the Boston Gazette. Susanna makes a trip to the boat, named Phillis where Susanna purchases the frail, dingy African girl, naming her after the boat.

In just a year, Susanna’s daughter, who is the same age as Phillis, teaches Phillis to read English (4). At eleven, Phillis writes her first poem. Within ten years of her arrival in Boston, Phillis becomes an internationally known poet. Her work even catches the attention of General George Washington. On February 28, 1776, General Washington praises her poetry, writing to

Phillis, “The style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your poetical talents”(5). Even though Phillis Wheatley is displaced, even though she is in a foreign place, she is still elevated to a high place. Even though she is displaced, her impact is still felt.

Just as Phillis Wheatley is displaced, so also John is displaced. In Revelation 1:9, John discloses that he has been exiled to the island of Patmos for proclaiming that Jesus is Lord. A small island ten miles long and six miles wide, located thirty- seven miles from the mainland, Patmos is also the destination of banished political prisoners (6). Nevertheless, even though John has been banished to Patmos, all is not lost, because, according to Revelation 1:10, Patmos is where John receives the vision to write the book of Revelation.

The influence of this compelling book has reached beyond John’s earliest

readers to our world today. For example, several hymns sang in Christian worship

today are inspired by Revelation. One of the most popular is influenced by

Revelation 4:8:

Holy, Holy, Holy! Lord God Almighty

Another beloved song of the church, “Revelation 19:1,” modifies the verse after which it is named:

Hallelujah!

Salvation and glory

Honor and power unto the Lord our God

For the Lord our God is mighty

Yes, the Lord our God is omnipotent

The Lord our God

He is wonderful (7)

Thus, even though John is displaced, his impact is still felt.

In the crafting of this vision, John makes use of symbolism, such as an edible bittersweet scroll (10:9–10), a red dragon that spits out a raging river (12:13–15), and a seven-headed beast with ten horns (17:3). In keeping with the spirit of John, let us now employ symbolism to illumine the limitations of displacement.

A couple years ago, while I’m working on a sermon in the library, I walk to my car for a bottle of water. As I stroll across the parking lot, I notice a batch of grass growing through a crack in the ground. On my way to the car, I pause to tell the grass, “You’re not supposed to be growing over here. You’re supposed to grow with the other grass over there. You’re displaced.”

The insightful grass answers, “Well, Larry, what you may not know is that the pavement actually holds moisture beneath the surface, kind of like mulch. So even though I may seem displaced, this is the perfect place for me to grow.”

I reply, “Stop playing!”

The grass retorts, “I’m serious. Even though I’m not supposed to be right here, even though I did not ask to be right here, God has still blessed me and nurtured me—right here.”

As it is with the grass, as it is with Phillis Wheatley, as it is with John, so it is with us. Even when it seems as if we are displaced, out of place, misplaced, or in a bad place, it is important to remember that God can still carry out God’s purpose for us in any place.

1 Henry Louis Gates, Jr., The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America’s First Black Poet and Her Encounters with the Founding Fathers (Basic Civitas Books: New York, 2010), 5–15.

2 Anthony B. Pinn, Introducing African American Religion (Routledge: New York, 2013), 18–19.

3 Gates, Trials of Phillis Wheatley, 16–19.

4 Ibid., 18–19.

5 Ibid., 38.

6 Craig R. Koester, Revelation and the End of All Things (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 2001), 52.

7 Stephen Hurd, “Revelation 19:1,” released October 3, 2006, track 21 on My Destiny, Integrity Music, 2010, Apple Music.

Rev. Dr. Larry L. Enis is the founding pastor of New Beginnings Church in Mechanicsville, VA. He also teaches preaching at Union Presbyterian Seminary.